Ascent from the Underworld

The sound of loud conversations and arguments over who got what piece of the turkey at Thanksgiving were very typical in my house but once all the plates were filled and the eating started, the noise started to subside. It was during this lull that my mother turned to me and said "Craig came home today and it might be nice if you went to visit him". I knew Craig had returned. I saw the feature story on him in the Sunday newspaper.

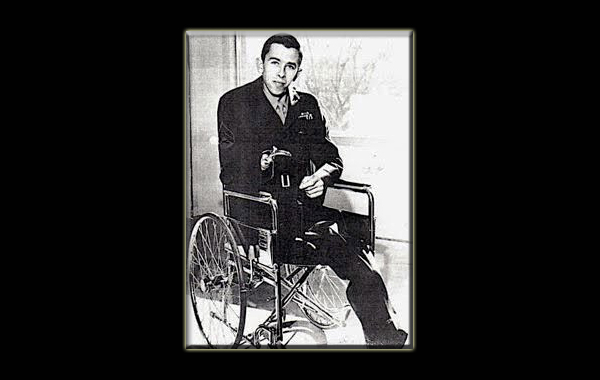

They had a big picture of him sitting in his wheelchair wearing his Marine uniform. Both legs of his trousers were folded under as he lost one leg at the knee and the other at the hip. The empty left sleeve of his jacket was folded up and pinned at the shoulder. Sitting prominently among the campaign ribbons on his chest was a Bronze Star with a "V" for valor. He gazed into the camera with little expression. The article discussed his wounds and stories about his boyhood. They interviewed teachers and peers who remarked about what a great track star he was and the all potential he had. He was full of dreams they said of a bright future and how tragic it was that he would lose three limbs in the war. The article did not even come close to the Craig that I knew.

"I suppose I will." I said to my mom.

My father leaned forward in his seat and with stern look and his finger pointed directly at me he said, "You don't have to see him if you don't want to. This your last leave before going overseas and seeing Craig is not going to do you any good. See your friends and enjoy yourself."

But I did go see Craig. I had to, he was my friend. We were friends in high school and both of us in the Marines gave us something more intimate than being just buddies. He was my friend and a fellow Marine in trouble and to leave without even visiting him would have been an unconscionable disregard of his sacrifice.

We joined the Marines a year apart. The newspaper didn't discuss how he ended up joining at age seventeen after dropping out of high school. He had poor grades, difficulties at home, and had not run track since 9th grade. He led a troubled life. In 1965, at seventeen, he left for the Marines and at nineteen went to war.

We spent some days together drinking. We talked and laughed about our crazy friends and the experiences in high school. The drinking, fighting, the police and the mayhem we caused. In and out of our conversations he would pause and recount in detail the area, the action and the mine explosion that vaporized most of his body. He said it all happened so fast. One second he was trying to find his way out of village through a mine field when an explosion nearby caused him to move his foot just a couple of inches too far and boom! He stepped on one. But Vietnam was far away for both of us so we lost ourselves in the alcohol that afternoon and for a while it seemed as if he never left home. The fun quickly disappeared, however, when we went out in public.

When Craig wheeled his chair into a bar, it seemed that everything stopped. The lights would continue to blink, and the jukebox kept playing but the activity stopped, and it would become so quiet that you could hear the pool balls clicking in the back room.

His anger was always just under the surface, and it would start to rise as the looks of the people gave evidence to all that he was a freak. He could see the looks of pity and aversion that people showed when they were near to him. He made them uncomfortable, and he knew it. No one knew what to say to him.

The welcome sign over the bar door was not for him. He knew too, that the pretty girls would no longer be part of his life and that they would never come back. He resented that the people around him were drinking and laughing while he and men like him were getting shot and stepping land mines. His drinking would accelerate, and as he verbally provoked people looking for a fight, he would get out of control. He wanted no intercession from me on his behalf. It didn't matter if anyone wanted to fight, it only mattered that he did. Breaking a pool cue on the edge of a pool table, running his wheelchair into someone or brandishing his pistol was evidence of the pain and conflict in a man who was down to the last 85 pounds of his body.

No one would try to control or reason with him. The police would simply let him go. He was a hurricane that you had to wait out until it exhausted itself. The pain from his wounds and psyche would become more visible as he tried to overcome his handicaps and fail. I have never seen at any time in my life more pain in a human being than that of my friend. His emotions were uncontrollable, and he was unable to understand why they didn't let him die on the battlefield and avoid coming home to this half-life that awaited him.

We talked a lot about what was going on in Vietnam, and though I tried to remember that not all men die or come home like Craig, the reality and consequences of war were hard to ignore. I began to question the wisdom of enlisting and worried about what was ahead of me. I developed both doubt and fear. I understood now why my father cautioned me about making this visit to see him.

In April 1983, the hurricane finally blew itself out. Craig Albers died at the age of thirty-three and is buried in the Willamette National Cemetery in Portland Oregon.

There was one more friend I had to say goodbye to before leaving for Camp Pendleton. Like Craig, he was in the news only he was serving eight years in the state penitentiary. His mother drove me down on visiting day. I remember walking under the guard towers and through all the fencing and barbed wire walls to reach the visiting room. At our first check point we had to sign a release acknowledging that there was a "no hostage policy" and if taken hostage by a prisoner, the prison would not negotiate for our release. Moving from one chamber to the next ended each time with the cold boom of steel slamming behind us. The loud click of the lock as the bars closed behind us took us deeper and deeper into the prison. There was no way out. Deep into its interior we were escorted into a large cafeteria and seated. A guard brought him out to see us and stood by to keep a watchful eye on him while we talked. The room was full of noisy conversation as babies cried, people spoke with loud voices. Within the concrete walls, the acoustics bombarded our ears with the cacophony of a chorus of noise.

He seemed changed as we spoke. We talked about Craig and what was going on at home. He described to his mother how the warden showed interest in his potential and was giving him better jobs. He attended church on a regular basis which pleased her tremendously. He reported the various compliments that he was getting in his reports and how hopefully he would be released early and come and get a job.

She was very pleased to hear he was doing so well. She had spent a lifetime visiting him in places like this and wanted to see her boy lead the happy Christian life. It was a wish she would never live to see but for the moment her grief and pain was relieved. She became emotional and asked the guard if she could use the ladies room. He pointed her to one at the other end of the room, and she left us to talk.

I told him I was glad to hear that he was changing so much when he interrupted me and said: "That's bullshit." "I am doing well. I get on the outside now and buy and sell dope. I make money selling the stuff I can smuggle back in here." He talked about his plans when he got out, and it became real clear to me he was going to the same man when he got out as he was going in; a dangerous, violent, drug addicted criminal. He stayed that way and after many years of destruction and havoc, he went to his brother’s apartment one day, and while sitting on the edge of his brother’s bed, he stuck a shotgun in his mouth and pulled the trigger.

Driving home with his mother from the prison, I stared out at the countryside and tried to absorb the experiences I had on my leave. Now that I was at the end of it and due to be deployed to Ground Forces, FMF, Pacific, I wondered again about the wisdom of my enlistment. I had two choices out of high school. Stay here or go in the Marines and possibly end up like Craig. I tried to reason the answer out, but it escaped me. What came instead was feeling that regardless of what was waiting for me in my future I did the right thing in leaving home. Even though it was uncertain, it was still a chance to break out.

During the summer of my junior year of college I read a poem by Robert Frost titled "The Road less Traveled," and the questions about my decision in 1966 were answered.

"I shall be telling this with a sigh

Somewhere ages and ages hence:

Two roads diverged in wood,

And I—

I took the one less traveled by,

And that has made all the difference."

Bob McLalan

1 Response